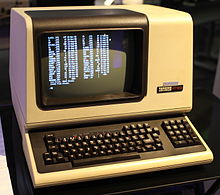

While early IBM PCs had single color green screens, these screens were not terminals. The screen of a PC did not contain any character generation hardware; all video signals and video formatting were generated by the video display card in the PC, or (in most graphics modes) by the CPU and software. An IBM PC monitor, whether it was the green monochrome display or the 16-color display, was technically much more similar to an analog TV set (without a tuner) than to a terminal. With suitable software a PC could, however, emulate a terminal, and in that capacity it could be connected to a mainframe or minicomputer. The Data General One could be booted into terminal emulator mode from its ROM. Eventually microprocessor-based personal computers greatly reduced the market demand for conventional terminals.

In the 1990s especially, “thin clients” and X terminals have combined economical local processing power with central, shared computer facilities to retain some of the advantages of terminals over personal computers:

Today, most PC telnet clients provide emulation of the most common terminal, the DEC VT100, using the ANSI escape code standard X3.64, or could run as X terminals using software such as Cygwin/X under Microsoft Windows or X.Org Server software under Linux.

Since the advent and subsequent popularization of the personal computer, few genuine hardware terminals are used to interface with computers today. Using the monitor and keyboard, modern operating systems like Linux and the BSD derivatives feature virtual consoles, which are mostly independent from the hardware used.

When using a graphical user interface (or GUI) like the X Window System, one’s display is typically occupied by a collection of windows associated with various applications, rather than a single stream of text associated with a single process. In this case, one may use a terminal emulator application within the windowing environment. This arrangement permits terminal-like interaction with the computer (for running a command line interpreter, for example) without the need for a physical terminal device; it can even allow the running of multiple terminal emulators on the same device.

終端裝備的顯示和輸入處理邏輯都在本身內(nèi)完成,無(wú)需主機(jī)的參與,本身是1個(gè)完全的系統(tǒng),通過(guò)串口與主機(jī)通訊。

而PC上的鍵盤和顯示器都需要主機(jī)本身來(lái)驅(qū)動(dòng),不能脫離主機(jī)而單獨(dú)發(fā)揮作用。

在計(jì)算機(jī)發(fā)展的初期,計(jì)算機(jī)主要用來(lái)計(jì)算,供大多數(shù)人來(lái)使用。因而,終端被發(fā)明出來(lái),通過(guò)串口可以遠(yuǎn)程連接到主機(jī),然后對(duì)主機(jī)進(jìn)行操控。

后來(lái)到了PC時(shí)期,計(jì)算機(jī)和終端進(jìn)行了密切結(jié)合,計(jì)算機(jī)除本來(lái)的計(jì)算任務(wù)外,還完全驅(qū)動(dòng)著直接連接的鍵盤和顯示器,終真?zhèn)€概念不再存在。

其中PC的直接控制鍵盤和顯示器的功能,非常切合原來(lái)終真?zhèn)€概念。事實(shí)上,使用PC完全可以摹擬原來(lái)的硬件終端裝備,而且現(xiàn)在這類摹擬已完全取代了原來(lái)的硬件終端裝備。

PC除控制顯示器和鍵盤鼠標(biāo)以外的其他計(jì)算能力,則相當(dāng)于原來(lái)的“計(jì)算機(jī)”。

其實(shí)不是所有計(jì)算機(jī)都像PC1樣把顯示控制作為主要功能,例如工業(yè)控制領(lǐng)域的計(jì)算機(jī),主要功能就是完成各種工業(yè)裝備的控制而不是顯現(xiàn)多么美好的人機(jī)界面。所以界面交互部份完全可以獨(dú)立出來(lái),成為“終端”。

這類通過(guò)串口就能夠控制的帶觸摸功能的控制屏非常流行。

固然,這與傳統(tǒng)終真?zhèn)€概念非常類似了。

隨著云計(jì)算的普及,大量的運(yùn)算又開始從PC轉(zhuǎn)向數(shù)據(jù)中心里的服務(wù)器上。PC上僅僅運(yùn)行像閱讀器這樣的終端軟件,真實(shí)的計(jì)算是在遠(yuǎn)程的計(jì)算機(jī)上完成的。

這在概念上就相當(dāng)于,每一個(gè)PC都是1臺(tái)終端,連接到了“云”上的計(jì)算機(jī)。

終端和計(jì)算機(jī)又1次進(jìn)行了分離。

傳統(tǒng)終端和主機(jī)直接的通訊協(xié)議主要是ANSIC編碼的文本,所以也叫“文本終端(Text Termainal)或ANSI終端”,通訊的媒介主要是串口。

云時(shí)期的“終端”和主機(jī)的通訊協(xié)議依然是可讀文本,只不過(guò)編碼更多的采取了UTF⑻,協(xié)議規(guī)范叫做HTML,通訊媒介則主要是互聯(lián)網(wǎng)了。

計(jì)算機(jī)各部份功能,分久必合,合久必分,終究“分”會(huì)成功!“分離”代表著模塊化,代表著規(guī)范,代表著合作。只有分離,才能帶來(lái)更多企業(yè)的合作,才能帶來(lái)專注。

通訊協(xié)議文本化是絕對(duì)的王者,2進(jìn)制沒(méi)法望其項(xiàng)背。1個(gè)人機(jī)皆可讀的、與軟硬件平臺(tái)無(wú)關(guān)(想一想大小真?zhèn)€字節(jié)序問(wèn)題和各種數(shù)據(jù)類型的2進(jìn)制不統(tǒng)1情況吧)的文本化協(xié)議絕對(duì)勝過(guò)單純的2進(jìn)制流。文本化是Unix編程哲學(xué)的重要組成部份。從Unix的配置文件、日志文件到終真?zhèn)€通訊協(xié)議,再到云時(shí)期html,xml,json,文本始閃爍著耀眼的光芒!

傳統(tǒng)的硬件終端裝備已滅亡,但是終真?zhèn)€概念、功能、習(xí)慣幾近沒(méi)有改變,依然以各種”偽終端“的情勢(shì)成為Unix系統(tǒng)的重要組成部份。理解終真?zhèn)€概念是理解Unix系統(tǒng)的基礎(chǔ),也是理解Unix哲學(xué)的1個(gè)優(yōu)秀案例。